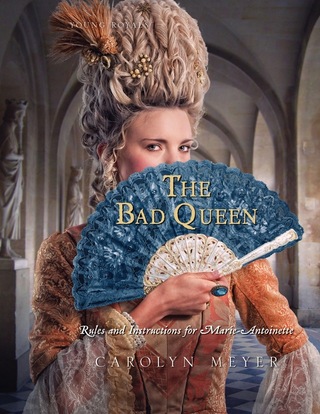

The Bad Queen: Rules and Instructions for Marie-Antoinette

Marie-Antoinette is given endless instructions before she leaves Austria at the age of fourteen to marry the dauphin of France. In her new home at the grand palace of Versailles, her every move in scrutinized by the cruel and gossipy members of the French court. Marie-Antoinette tries to adhere to their stifling rules of etiquette, but sometimes this fun-loving young woman can't help but indulge herself with scandalous fashions, taboo recreations, elaborate parties--and even a forbidden romance.

Rule No. 1: Marry Well

The empress, my mother, studied me as if I were an unusual creature she’d thought of acquiring for the palace menagerie. I shivered under her critical gaze. It was like being bathed in snow.

"Still rather small, but I suppose she’ll grow. Her sisters did," my mother said half to herself. She caught my eye. "No bosom yet, Antonia?"

I shook my head and stared down at my naked toes, pale as slugs. "No, Mama."

Swathed in widow’s black, the empress frowned at me as if my flat chest were my own fault. "She’s no beauty, certainly," she said, speaking to my governess, Countess Brandeis. "But pretty enough, I think, to marry the dauphin of France." She signaled me to turn around, which I did, slowly. "My dear countess, something must be done about her hair!" my mother declared. "The hairline is terrible -- just look at it! And her teeth as well. The French foreign minister has already complained that the child’s teeth are crooked. King Louis has made it quite clear that everything about my daughter must be perfect before he will agree to her marriage to his grandson."

Brandeis inclined her head. "Of course, Your Majesty."

"One thing more, Antonia," said my mother sharply. "You must learn to speak French -- beautifully. And this, too: from now on you are no longer Antonia. You are Antoine." She dismissed us with a wave and turned her attention to the pile of official papers on her desk.

Antoine? Even my name must change? I gasped and groped for an answer, but no answer came, just one dry sob. The countess rushed me out of the empress’s chambers before I could burst into tears. That would be unacceptable. Mama didn’t allow her daughters to cry.

I’ve thought of this moment many times. And I think of it again, no longer attempting to hold back my tears after all that has happened to me since then....(continued below)

Bookworks in Albuquerque borrowed the gorgeous pink gown on the left

from the Santa Fe Opera and created a clever cut-out

so we could pose for our "portraits."

What would the king of France have thought about this!

Author's Note

“Let them eat cake.”

The French people were starving, there was no bread, and Queen Marie-Antoinette, dressed in expensive silks and diamonds with her hair in a towering pouf, flicked her jeweled fan and pronounced the famously disdainful sentence.

That’s how the story goes. The fact is, she never said it. Arguments have been waged for years about the source of the story—exactly who said what, the definition of “cake,” the circumstances under which the words were uttered, and if they were even uttered at all. The often-repeated remark is part of the myth of Marie-Antoinette as the cruel queen whose behavior sparked the French Revolution.

But was she as heartless as she is usually portrayed? I wondered about that, especially after I saw Sophia Coppola’s 2006 movie, Marie Antoinette. I was curious about who this bad queen really was and what she did that made her one of the most hated queens in history.

The Bad Queen, like my other novels, is a work of historical fiction. I’m often asked if the books I write about famous queens—Bloody Mary, Anne Boleyn, Catherine de’ Medici, and now Marie-Antoinette—are “true.” The answer is that they are based on the known facts. But as anyone who has studied history has learned, the “facts” are often debatable or simply unknown. Often there is no proof, just speculation and educated guesswork. The history in all my books is as accurate as my research can make it. I have not invented a single character in this novel. I have woven the actual historical figures and the known facts into a fictional framework. Much of the dialogue is based on quotations—translated from French, of course—found in historical accounts.

But I have used my imagination to bring certain events to life; I’ve also chosen to let Marie-Antoinette tell her own story, expressing her thoughts and feelings in a voice that I hope is much like hers--until the last section, when the voice is her daughter's. That is what makes The Bad Queen a work of fiction rather than biography.

No. 1: Marry well (continued)

My mother was known to all the world as Maria Theresa, Holy Roman Empress, archduchess of Austria, queen of Hungary and Bohemia, daughter of the Hapsburg family that had ruled most of Europe for centuries. Mama believed the best way to further the goals of her huge empire was not through conquest but through marriage. I’d heard her say it often: Let other nations wage war—fortunate Austria marries well. She used us, her children, to form alliances.

There were quite a lot of us to be married well. My mother had given birth to sixteen children—I was the fifteenth—and in 1768, the year in which this story begins, ten of us were still living. Three of my four brothers had been paired with suitable brides. The eldest, Joseph, emperor and co-ruler with our mother since Papa’s death, was twenty-seven and had already been married and widowed twice. Both of his wives had been chosen by our mother. Joseph still mourned the first, Isabella of Parma, with whom he had been deeply in love, but not the second, a fat and pimply Bavarian princess whom he had detested from the very beginning. I was curious to see if Mama would make him marry well for a third time.

Next in line for the throne, Archduke Leopold was married to the daughter of the king of Spain. Then came my brother Ferdinand, thirteen, a year older than I, betrothed since he was just nine to an Italian heiress. No

doubt he would soon marry her. The youngest archduke, chubby little Maximilian—we called him Fat Max—was not on Mama’s list for a wife. He was supposed to become a priest and someday an archbishop.

Of my five older sisters, Maria Anna was crippled and would never have a husband, and dear Maria Elisabeth had retired to a convent after smallpox destroyed her beauty. (All of us archduchesses had been given the first

name Maria—an old family tradition.) My other sisters had been found husbands of high enough ranks.

Maria Christina, called Mimi, was my mother’s great favorite, and somehow she had been allowed to marry the man she adored, Prince Albert of Saxony. Lucky Mimi, one of the most selfish girls who ever lived!

Maria Amalia was madly in love with Prince Charles of Zweibrücken, but Mama opposed the match—he wasn’t rich enough or important enough—and made Amalia promise to marry the duke of Parma. Amalia didn’t like him at all, and she was furious with Mama.

“Mimi got to marry the man she loved, even though he has neither wealth nor position,” Amalia stormed, “and Mama gave her a huge dowry to make up for it. So why can’t I marry Charles?”

Silly question! We all knew she had no choice. Only Mimi could talk Mama into giving her whatever she wanted. Maria Carolina, the sister I loved best, had to marry King Ferdinand of Naples. This was the final chapter of a very sad story: two of our older sisters, first Maria Johanna and then Maria Josepha, had each in turn been betrothed to King Ferdinand. First Johanna and then Josepha had died of smallpox just before a wedding could take place. Ferdinand ended up with the next in line, Maria Carolina. He may have been satisfied with the change, but Carolina hadn’t been.

“I hear he’s an utter dolt!” Carolina had wailed as her trunks were being packed for the journey to Naples. She’d paced restlessly from room to room, wringing her pretty white hands. “And ugly as well. I can only hope he doesn’t stink!”

It didn’t matter if he stank. We had been brought up to do exactly as we were told, and Mama had a thousand rules. “You are born to obey, and you must learn to do so.” (This rule did not apply to Mimi, of course.)

Though she was three years older than I, we had grown up together. We had also gotten into mischief together, breaking too many of Mama’s rules (such as talking after nightly prayers and not paying attention to our

studies), and our mother had decided we had to be separated. In April, when the time came for her to leave for Naples, Carolina cried and cried and even jumped out of her carriage at the last minute to embrace me tearfully

one more time. I missed her terribly.

That left me, the youngest daughter, just twelve years old. I knew my mother had been searching for the best possible husband for me—best for her purposes; my wishes didn’t count. Now she thought she had found him: the dauphin of France. The Austrian Hapsburgs would be united with the French Bourbons. But she also thought I didn’t quite measure up.

After my mother’s cold assessment, Brandeis led me, sobbing, through gloomy corridors back to my apartments in the vast Hofburg Palace in Vienna. She murmured soothing words as she helped me dress—I had appeared in only

a thin shift for Mama’s inspection—and announced that we would simply enjoy ourselves for the rest of the day.

“Plenty of time tomorrow for your lessons, my darling Antonia,” the countess said and kissed me on my forehead. She hadn’t yet begun to call me Antoine, and I was glad.

Her plan was fine with me. Neither Brandeis nor I shared much enthusiasm for my lessons. I disliked reading—I read poorly—and avoided it as much as I could. Brandeis saw no reason to force me. She agreed that my handwriting was nearly illegible—I left a trail of scattered inkblots—and allowed me to avoid practicing that as well. My previous governess had also given up the

struggle, helpfully tracing out all the letters with a pencil so I had only to follow her tracings with pen and ink. When my mother discovered the trick, the lady was dismissed. Brandeis didn’t resort to deception, but neither did she do much to correct my messy handwriting.

“You’ll have scant use for such things,” said my governess now. She shuffled a deck of cards and dealt a hand onto the game table. “You dance beautifully—who can forget your delightful performance in the ballet to celebrate your brother Joseph’s wedding? Your needlework is exquisite, and your music tutor says you show a talent for the harp. What more will you need to know? A member of the court will read everything to you while you stitch your designs, and a secretary will write your letters for you. You won’t even have to think about it. You’ll have only to be charming and enjoy yourself, when you become the queen of France.”

“Queen of France?” I exclaimed, a little surprised. I hadn’t thought much beyond marrying the dauphin, whoever he was. “Am I truly to be queen of France, Brandeis?”

“You will someday, if everything goes according to plan. The young man your mother has chosen for you to marry is next in line for the throne. The future wife of the dauphin will be the dauphine, and when old King Louis the Fifteenth dies and his grandson the dauphin becomes king, you, my sweet Antonia, will become his queen.” She smiled and sighed. “Everyone knows that Versailles is the most elegant court in all of Europe, and you shall be its shining glory!”

Queen! The idea thrilled me. My brothers and sisters had been matched with royalty from several other countries in Europe, but France was the most important—I understood that much—and that made me important, more important than my snobbish sister Mimi! Being married to the prince of Saxony wasn’t much to brag about, compared to being queen of France. I pranced around my apartments with my nose in the air, as though I already wore a crown. Countess Brandeis swept her new sovereign a curtsy so deep that her nose touched the floor. I laughed and twirled and clapped my hands.

Then I remembered my mother's pronouncement: everything must be perfect."Oh, dear Brandeis, what about my hair?" I cried. "And my teeth? Mama says they're not pleasing to the French king. And you"re supposed to call me Antoine."

"I imagine a friseur will be sent to dress your hair," said Brandeis with a careless shrug, "though it looks fine enough to me--a mass of red-gold curls, what could be prettier? And I've heard that crooked teeth can be fixed as well as unruly locks. Meanwhile, I suggest you simply put all of this out of mind." She picked up her cards and arranged them."Now, shall I draw first, or shall you?"

I did as my governess suggested and succeeded in winning a few pfennig from her. The next day we bundled ourselves in furs and rode through Vienna in a sleigh shaped like a swan and drawn by horses with bells jingling on their harnesses. We returned to my apartments in the Hofburg to sip hot chocolate ad forget the unpleasant business of lessons and other worrisome matters. Brandeis always neglected to call me Antoine. I was still her dear Antonia--until one day when all our pleasant enjoyment came to an end.